This cartoon's soundtrack is "Doctor Blind" by Emily Haines and the Soft Skeleton. Listen here via CBC Radio3.

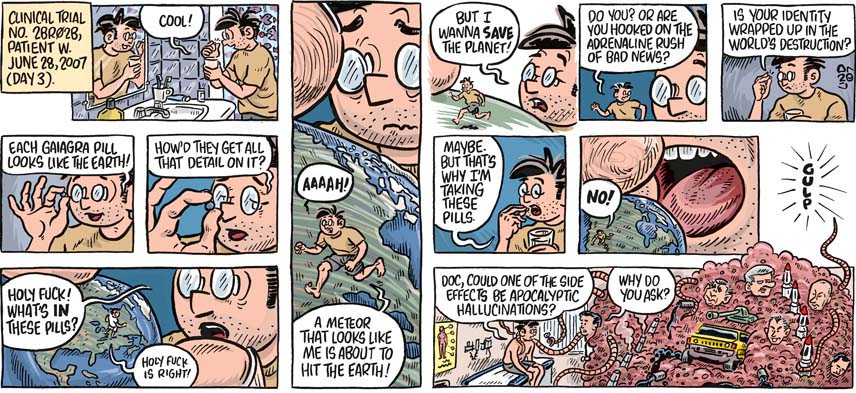

This is the first time I've set up a cartoon as three rows. I just needed more panels for the zooming-in effect. I drew it some weeks ago, just after the revelation that Putin was ready to have a showdown with Bush over Bush's anti-missile plan. Things seem to have simmered down somewhat since then. Or maybe I'm just enjoying the summer and, unlike Horst, having fewer apocalyptic hallucinations than usual.

An interview in Salon with physicist Paul Davies about the nature of the universe caught my eye this week. I've just now read it. Some mind-blowing stuff that throws a wrench into all creationist arguments (even distantly creationist ones), while insisting that our universe has a reason for being the way it is. A central problem with physics is that there is still no explanation as to why the laws are the way they are. (There are half a dozen fundamental laws which, if slightly different, would make life in this universe impossible.) Except that if, as many physicists believe, there are multiple universes, and the one we're in happens to have the physical laws constructed "just so."

Fascinating reading. An excerpt:

Standard quantum physics says that if you make an observation of something today -- it might just be the position of an atom -- then there's an uncertainty about what that atom is going to do in the future. And there's an uncertainty about what it's going to do in the past. That uncertainty means there's a type of linkage. Einstein called this "spooky action at a distance."

But what's so hard to fathom is that this act of observation, which has been observed at the subatomic level, would affect the way matter spread right after the big bang. That sounds awfully far-fetched.

Well, it's only far-fetched if you want to think that every little observation that we perform today is somehow micromanaging the universe in the far past. What we're saying is that as we go back into the past, there are many, many quantum histories that could have led up to this point. And the existence of observers today will select a subset of those histories which will inevitably, by definition, lead to the existence of life. Now, I don't think anybody would really dispute that fact.

What I'm suggesting -- this is where things depart from the conventional view -- is that the laws of physics themselves are subject to the same quantum uncertainty. So that an observation performed today will select not only a number of histories from an infinite number of possible past histories, but will also select a subset of the laws of physics which are consistent with the emergence of life. That's the radical departure. It's not the backward-in-time aspect, which has been established by experiment. There's really no doubt that quantum mechanics opens the way to linking future with past. I'm suggesting that we extend those notions from the state of the universe to the underlying laws of physics themselves. That's the radical step, because most physicists regard the laws as God-given, imprinted on the universe, fixed and immutable. But Wheeler -- and I follow him on this -- suggested that the laws of physics are not immutable.

10 Years Ago This Week: July 2, 1997

Horst is asked into his boss's office. Horst, of course, assumes the worse. The meeting ends in Horst losing consciousness. (Back in the 80s, I worked in an office where one guy, Hugh, wore cologne you could smell coming. The resemblance is not coincidental.)

|